By Jenifer Frank

Melanie Stengel Photo.

Fanny Quille with her children Rocio Valladares, 2; Beverly Valladares,7; Angel Valladares, 14; and Anthony Valladares, 7 months, in their Wood Avenue apartment in Bridgeport. Their apartment was inspected after Rocio’s 2-year-old checkup, when she was found to have high levels of lead in her blood. Lead was found in the peeling paint at the exterior of the house, which was built in 1911.

It wasn’t until Bridgeport lead inspector Charles Tate stepped outside the house on Wood Avenue that he saw, immediately, where 2-year-old Rocio Valladares was being poisoned.

The paint around a window at the back of the house was deteriorating. Beneath the window was Rocio’s favorite play area, a sloping basement door that was the perfect ramp for an energetic toddler. Next to the basement door was a patch of dirt where she loved to scratch with sticks. White chips of paint were visible in the dirt.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says 5 micrograms or higher of lead per deciliter of blood constitutes lead poisoning.

Rocio’s mother, Fanny Quille, said her daughter’s blood tests show a lead count of over 70.

Lead poisoning, a major systemic crisis, damages the health and development of hundreds of thousands of children across the U.S. every year, including thousands in Connecticut.

Although Connecticut has worked hard in its fight against COVID-19, its efforts against the much older plague of lead poisoning have been halfhearted.

“Unfortunately, Americans, in typical style, tend to react to very dramatic things, but they don’t tend to react to the chronic stories,” said Yale pediatrician Carl R. Baum, M.D., director of Yale’s Lead Poisoning And Regional Treatment Center.

“For the most part, lead is an ongoing problem, and some of the lead levels that were seen in [the Flint water crisis of 2014] are nothing compared to what we see in New Haven,” Baum said.

He referred to one young patient the Yale clinic has been treating for over a year whose peak lead level was 118 micrograms. “And we still haven’t gotten it down to an acceptable level.”

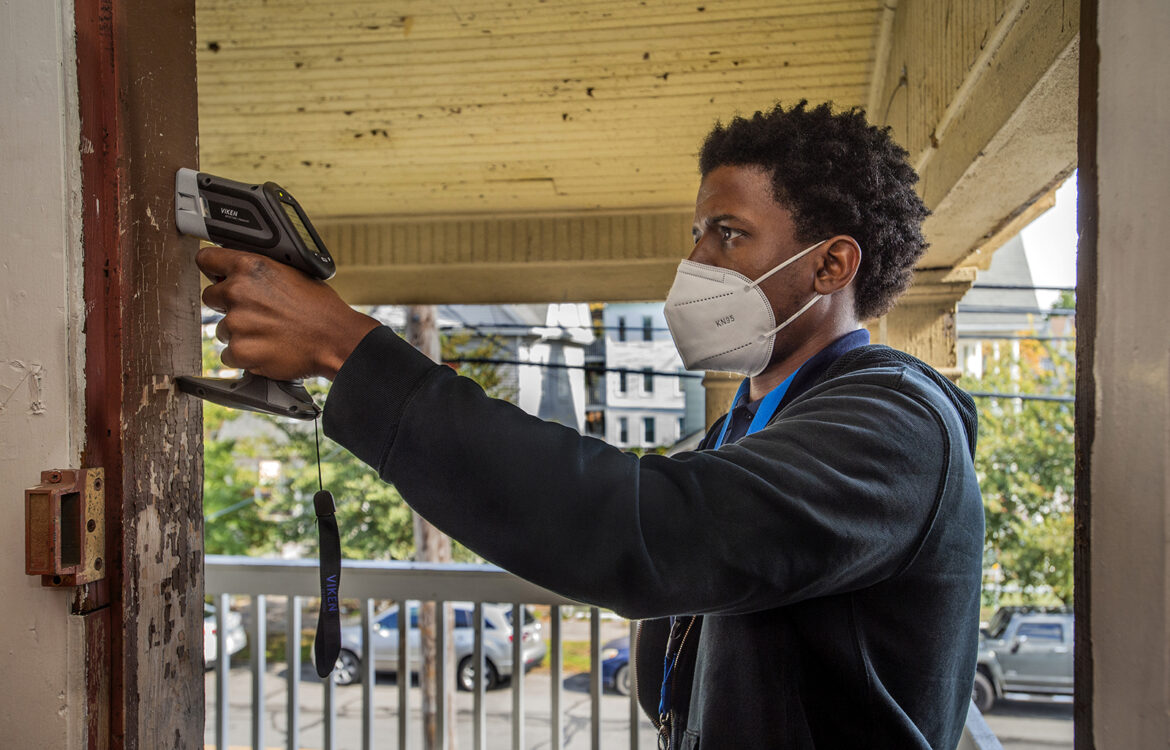

Melanie Stengel Photo.

Investigator Charles Tate prepares to scan a doorway to a second-floor porch on Wood Avenue. The ceiling and railings are also peeling. Tate found high levels of lead in the paint.

The Connecticut Department of Public Health (DPH) has reported 14,000 cases of lead-poisoned children under 6 since 2012.

At least 2,000 children were poisoned every year from 2012 through 2016, DPH numbers show, with fewer cases reported in 2017 (1,665) and 2018 (1,332).

However, testing deficiencies and gaps in reporting by municipalities and medical providers mean the true number of lead-poisoned children in Connecticut is unknowable and almost certainly higher than DPH’s figures.

Then there’s the COVID-19 factor. Connecticut law requires children to be tested for lead twice before 3 years old. But Kaiser Health News recently reported “massive” reductions in lead testing in many parts of the country, including the Northeast. Lead blood tests are usually given at children’s 1- and 2-year-old checkups. Not only did the virus force many families to postpone or skip those visits, but people have also spent more time indoors, where children are most likely to be exposed to degrading leaded paint and lead dust.

One of the most poignant aspects of this crisis is that children are often poisoned by their own homes. The interior and exterior walls of hundreds of thousands of homes have undercoats of leaded paint, which wasn’t banned until 1978. As paint degrades, it chips and creates invisible leaded dust that can be inhaled or ingested by babies and toddlers as they become more active.

Connecticut children are also victims of the state’s weak lead inspection statutes, which reflects an extraordinary lack of urgency and concern for a problem that can cause permanent cognitive damage and neurological issues.

In 2012, in a major shift, the CDC stopped advising investigations into sources of poisoning based on a child’s lead level. Instead, the agency said, preventing any exposure to lead should be the priority because “No safe blood lead level in children has been identified.” It did, however, recommend case management if a child’s lead level was 5 micrograms or higher.

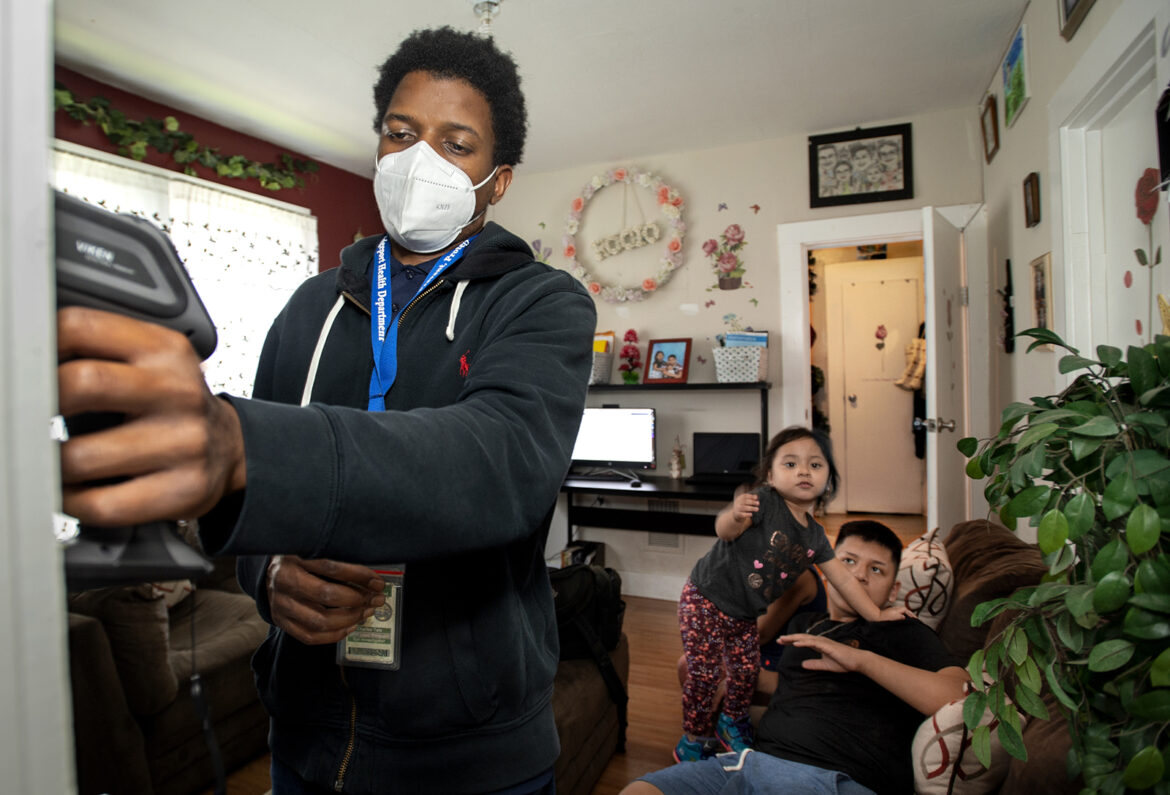

Melanie Stengel Photo.

Using an X-ray fluorescence (XRF) instrument, Bridgeport lead inspector Charles Tate prepares to scan an interior doorway of a multifamily Wood Avenue apartment. Looking on are Rocio Valladares, 2; and her brother Angel Valladares, 14.

In response, the other New England states toughened their laws and their actions.

In Maine, Vermont and Rhode Island, a 5-microgram lead test result now triggers an active investigation into how and where a child is being exposed. New Hampshire’s 7.5-microgram trigger is slated to drop to 5 in July, while Massachusetts requires investigation at 10 micrograms.

In an emailed statement, Jim Vannoy, an environmental health section chief at DPH, pointed out that Connecticut, in fact, adopted the CDC’s more stringent 5-microgram standard for action in lead-poisoning cases.

But state law doesn’t require active inquiry until a child’s lead blood count is at least three times — 15 micrograms in two tests given three months apart — or four times that level — 20 micrograms in a single test.

If a child shows 5 to 14 micrograms of the neurotoxin in a blood test, the state only requires a local health official to call the family or send them educational material about the dangers of lead.

Racial Inequities

Just as COVID-19 has spotlighted racial inequities in housing and health care nationwide, the lack of a concerted campaign against lead poisoning has racial and racist undertones.

Black children are poisoned at more than twice the rate of white children, and Hispanic children at 1½ times the rate, in part because Black and Hispanic families are more likely to live in older, substandard housing.

Despite Connecticut’s mandatory screening laws, and despite DPH efforts to reach Black and Hispanic families, just 13% of all children tested in 2017 were Black, its latest available breakdown of race and ethnicity numbers show. Twenty-six percent were Hispanic, and 61% were white.

Jennifer Haile, M.D., pediatrician at the Hartford Regional Lead Clinic, run by Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, said, “Just because we have [state] screening mandates doesn’t mean the pediatricians are actually doing it. The numbers are getting better, but they’re not great.”

David Rosner, professor at Columbia University and coauthor of “Lead Wars: The Politics of Science and the Fate of American Children,” said, “Lead is a major indicator of a much larger problem we have in our culture and the racism that pervades it.”

He added in an email,

“Do you think we’d allow this outrage to continue if it were suburban white children who were its primary victims?”

— David Rosner

An Insidious Enemy

For most of the 20th century, lead was added to paint to increase water-resistance and durability.

When ingested, lead’s damage can be irreversible. It’s especially harmful to babies and young children, who are at their peak period of brain development.

“Even low-level lead exposure can negatively impact a wide range of cognitive functions, such as attention, language, memory, cognitive flexibility, and visual-motor integration,” says a study on the website of the CDC’s Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry.

In June, social scientists at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio published the results of their 20-year study into the “downstream” effects of lead exposure.

After following more than 10,000 Cleveland children from birth through early adulthood, the scientists concluded, “[C]hildren with elevated lead levels in early childhood have significantly worse outcomes on markers of school success, and higher rates of adverse events in adolescence and early adulthood, compared to their non-exposed peers.”

Exposed babies and toddlers are lead sponges.

“Kids who are younger absorb lead at [many] times the rate adults will absorb it,” said Dr. Hilda Slivak, founder and former director of the Hartford Regional Lead Clinic.

They’re closer to the ground, and their breathing rates are higher than that of adults. Because they learn by crawling, touching and tasting, a floor with leaded paint chips and leaded dust is hazardous terrain.

One City Does It Right

Residents in poorer cities are particularly at risk. Indeed, New Haven, Bridgeport and Hartford consistently have some of the state’s highest numbers of reported cases.

Hartford’s streets are lined with older, poorly maintained homes, quintessential sources of lead poisoning. From 2012 through 2018, the DPH reported nearly 1,150 lead-poisoned children in the Capital City.

Yet because investigations are required only when children’s lead blood levels hit 15 or 20 micrograms, Hartford’s lead program looked into less than 12% of those cases, its own numbers show. In 2018, when DPH reported 109 children with lead poisoning, the program conducted 7 investigations.

Melanie Stengel Photo.

Rocio Valladares, 2, lies on the couch in the Bridgeport home her family rents. She was found to have elevated levels of lead in her blood. High levels of lead were found in the peeling exterior paint near what had been her favorite play area.

New Haven invariably has the highest number of cases, with 2,266 children reported lead-poisoned from 2012 through 2018.

It reported investigating 24% of properties linked to children with elevated lead levels in that period. New Haven’s lead program has been mired in controversy over the past few years, and has been sued for inadequate inspection and enforcement of lead laws. The longtime program director and the city’s public health director have resigned.

Typically, investigations and lead abatement actions in Connecticut are triggered only by reports of a poisoned child.

Except in Bridgeport.

“We don’t have to wait till kids hit 15 or 20 [micrograms],” said Audrey Gaines, who, as Bridgeport’s code enforcement officer, manages environmental health, housing code and lead prevention.

“If it’s not supposed to be there, why are you waiting for it to get higher before you help them?” Gaines said.

DPH reported 2,000 cases of lead-poisoned children in the state’s largest city from 2012 through 2018.

But after 2013, numbers dropped annually, and dramatically. In 2013, the city reported a high of 402 cases. In 2018, the city reported 137, a 66% decrease.

This accomplishment so surprised Tsui-Min Hung, the longtime epidemiologist of the DPH lead program, that she called Gaines to ask what her secret was.

Rather than relying on a child’s blood test to point inspectors toward a contaminated home, inspectors focus on “what the actual problem is, and that is the housing stock,” Gaines said.

The city reported inspecting nearly 1,900 buildings from 2012 through 2018.

“If our housing code inspectors find something that is in violation, and if there are children in those houses, they report it to my lead inspectors,” Gaines said. “It’s not rocket science. It’s just simply working cohesively together.”

Gaines also uses Connecticut’s Uniform Relocation Assistance Act to move families when necessary.

Melanie Stengel Photo.

Lead investigator Charles Tate shows the XRF results after scanning wood trim on the house. Levels above 1.0mg/cm squared are actionable. Levels here are 31mg/cm squared.

“If … a landlord is not capable or not willing or cooperative enough to want to make the repairs in that unit, to make that unit lead-safe, then we start sending him to court,” she said. “And, according to that Relocation Assistance Act, that family can be moved.

“You’ve got to go beyond state [lead] law,” Gaines said. “It’s not going to create the culture to be progressive, to get what you want done.”

She said the city is working to enroll the owner of Rocio’s Wood Avenue home into a federal housing program that will cover the cost of lead abatement or removal. “Once the enrollment process is completed, all work will be completed within a week,” she said.

Angel Valladares, Rocio’s 14-year-old brother, says his sister, who will be 3 in February, “knows a few random words, but is not really speaking.”

Their mother worries, he said, because Rocio cries a lot. “She’s always crying,” Angel said.

And these days, he said, his mother “barely brings her outside.”

This story was supported by the Fund for Investigative Journalism in Washington, D.C.

Support Our Work

The Conn. Health I-Team is dedicated to producing original, responsible, in-depth journalism on key issues of health and safety that affect our readers, and helping them make informed health care choices. As a nonprofit, we rely on donations to help fund our work.Donate Now

Related Stories

- As Lead In Children Persists, State Lawmakers Look To Tackle Risks With Connecticut children testing positive for lead at consistently high numbers, and millions of dollars thrown at the problem with tepid results, lawmakers may finally be stepping up to seek an effective solution. The Banking Committee is considering a bill that would create a task force to study better ways to finance the removal of the toxin from thousands of homes around the state.

More From C-HIT

- Disparities Connecticut’s Halfhearted Battle: Response To Lead Poisoning Epidemic Lacks Urgency

- Environmental Health Wildfire Smoke Likely To Have Increasing Impact On Health Of Those Already At Risk

- Fines & Sanctions Medical Board Disciplines Two Doctors

- Health Care Health Bills’ Failure A Bitter Pill For Health Care Proponents

- Health Q&A Question 4