By Elizabeth Heubeck

Photo by Melanie Stengel

Sharon Lovett-Graff, the manager of the Mitchell branch of the New Haven Free Public Library, helps Lydia Anderson, 3, with the computer. In the background Laura Anderson helps Lydia’s brother Ethan Anderson, 4 1/2, select books.

The Mitchell branch of the New Haven Free Public Library tries to be at the forefront of whatever products are trendy or new. That means offering e-books for patrons of all ages and providing computers for children who want to conduct research online or play games. But, according to branch manager Sharon Lovett-Graff, the library’s youngest patrons, and their parents, remain interested primarily in borrowing print books.

“At one time, we were all very nervous that e-books would take over. But not anymore,” said Lovett-Graff, who estimates that in the past year, the library checked out about 5,300 board books — thick, picture books aimed at pre-readers. “I don’t hear parents asking about e-books for toddlers,” she observed.

Recent research supports the reluctance of educational experts and parents to place electronic readers within reach of very young children.

The most recent study to scrutinize the emerging trend of e-readers for young audiences was published in the American Academy of Pediatrics’ (AAP) journal Pediatrics. The study, which analyzed interactions of 37 parent–toddler pairs while reading together electronic versus print books, found that parents and toddlers verbalized and collaborated less when parents read stories from e-readers than from the pages of a book. “This is an intriguing and important study that adds to what we know about the importance of reciprocal interactions between young children and their caregivers for healthy brain development,” said Linda Mayes, MD, professor of child psychiatry, pediatrics and psychology in the Yale Child Study Center.

Publication of these study results came sandwiched between recent recommendations by two major health organizations, both of which have imposed strict limits on screen time for very young children. This past April, the World Health Organization came out with its first-ever recommendation regarding screen time, asserting that children under 1 year of age should have virtually none. In 2016, the AAP released a lengthy statement on screen time broken down by age group, stating that children younger than 18 months should avoid use of all screen media other than video-chatting, and that screen time for children ages 2 to 5 should be limited to an hour per day of “high-quality programs.”

At the Oliver Wolcott Library in Litchfield, families who wanted to utilize computers or other technology in the children’s section are at a loss. The library deliberately maintains a technology-free children’s section that, anecdotally, appears to be bucking the technology-friendly trend of most libraries, statewide and throughout the nation.

Caroline Wilcox Ugurlu, PhD, a library assistant at the Oliver Wolcott Library, explains that while library professionals recognize that digital mediums are here to stay, some would like to hold off on exposing their young patrons to electronics for as long as is reasonably possible. “Many libraries are cognizant of the addictive nature and attention-scattering nature of digital mediums,” she said.

Reading Books Boosts Literacy

In addition to the heightened, richer vocabulary that books present to toddlers, the shared context of the experience is a key component to its value, explains Michael Coyne, professor of educational psychology at the University of Connecticut and co-director of the Center for Behavioral Education and Research. “It’s an opportunity for caregiver and child to engage in conversations and interactions unlike their day-to-day exchanges,” Coyne said.

While traditional books facilitate this engagement, he suggests that electronic devices may have the opposite effect. “The technology can become more the focus of the activity, rather than the content or the language,” Coyne observed.

His observations mirror those of other experts. For instance, an AAP statement asserted: “Interactive enhancements [as found in e-readers] may decrease child comprehension of content or parent dialogic reading interactions.” Pop-up ads, sound effects, and even the buttons on an electronic device are just some of its elements that can promote distraction. As a result, the distractions inherent to e-readers may replace or interfere with the spontaneous interactions that normally take place between parents and children while reading print books, suggests Yale’s Mayes.

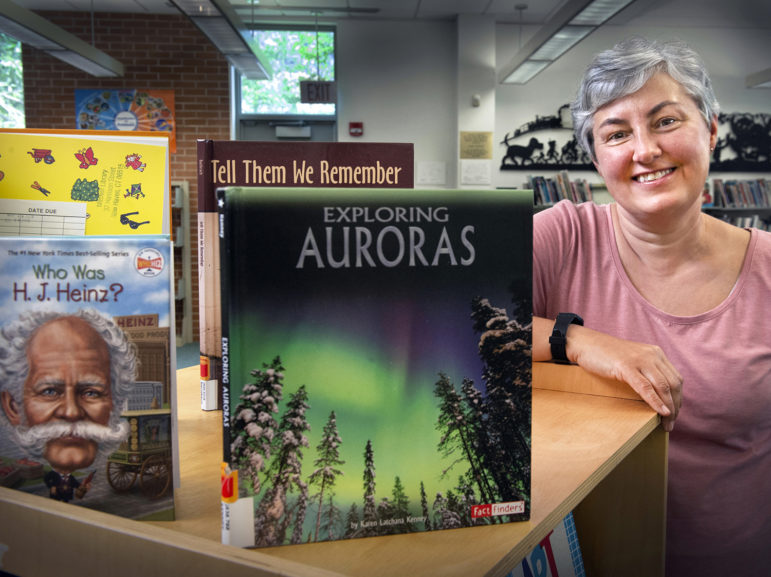

Photo by Melanie Stengel

Sharon Lovett-Graff and a selection of books at the New Haven Free Public Library’s Mitchell branch.

Literacy experts observe that many of the interactions that take place while reading print books together encourage “child-directed talk” — a key component to social and cognitive growth. Oliver Wolcott Library’s Ugurlu explains. “In child-directed talk, a caregiver and a child focus on each other, taking cues from one another’s facial expressions,” she said. On the contrary, notes Ugurlu, young children and adults tend to have more scattered focus when reading from an electronic device as opposed to a book. This runs counter to the conditions for reading, which Ugurla notes requires “deep focus.”

Does The Medium Matter?

It’s unlikely that toddlers are able to muster focus considered “deep,” especially in the absence of direct engagement with a caregiver. That could be why reading books with toddlers has, historically, been a shared activity. But with alluring electronic devices offering stories to children of all ages, that may be changing. And some bibliophiles are okay with that.

Sarah Briggs is a part-time librarian at Wallingford Public Library, a library/media specialist at Jonathan Law High School, a board member of the Connecticut Library Consortium, and mother to a 3- and 5-year-old. She does acknowledge the shared experience of reading with her young children as an “important bonding experience.” But she’s not too concerned with the medium used to convey the story.

“My children are very comfortable exploring phones, iPads, and those things. If there’s a story they want, they’ll pick the format based on what they’re looking for,” said Briggs, who believes that electronic devices can complement and supplement books, but not replace them.

“I just want to get them to sit and appreciate stories. The format, to me, is not so much the point,” Briggs said.

Others aren’t convinced that the format is inconsequential. Kyn Taylor, executive director of the Branford-based nonprofit Read to Grow, believes that reading print books to young children affords more spontaneity and variety than e-readers. “I serve up a question to you, then you respond, and it goes from there,” she said. “There seems to be a lot less of that when there’s a flat screen.”

Taylor does acknowledge that most of today’s parents grew up as “digital natives.” It’s only natural, then, that they would readily share information with their children via electronic devices. But she urges parents not to ditch print books altogether. “Let them turn the pages. Let them bite it. Let the book be an enhancement of your home,” Taylor said.

Support Our Work

The Conn. Health I-Team is dedicated to producing original, responsible, in-depth journalism on key issues of health and safety that affect our readers, and helping them make informed health care choices. As a nonprofit, we rely on donations to help fund our work.Donate Now