By Kate Farrish

Carl Jordan Castro Photo.

Rita Pompano of West Haven says she was a victim of elder abuse in 2011, when her husband Ralph tormented her and beat her daily for seven months before she was able to escape with her son’s help.

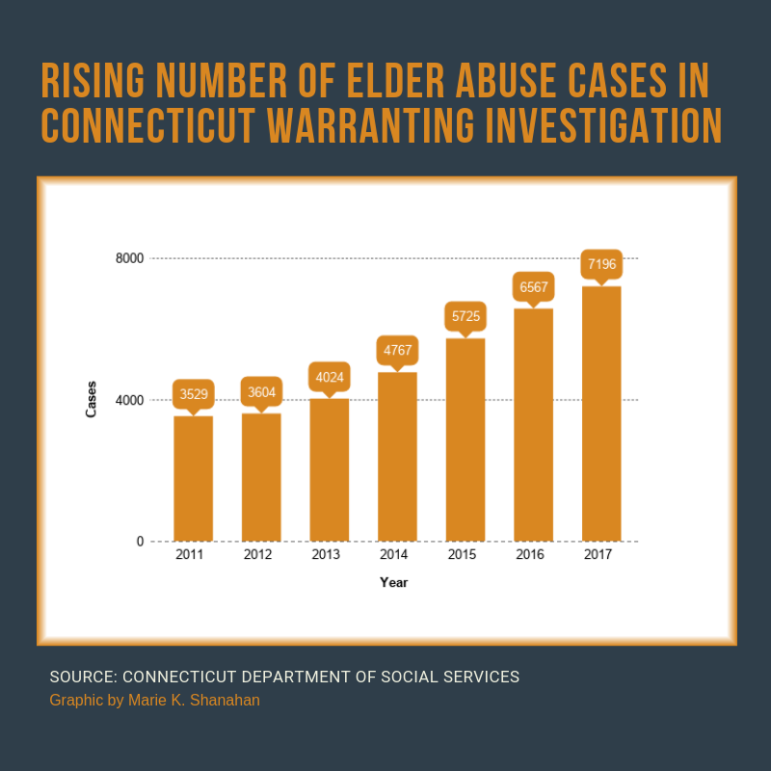

State investigations of elder abuse, ranging from neglect to emotional abuse to physical abuse, more than doubled in Connecticut between 2011 and 2017, from 3,529 to 7,196.

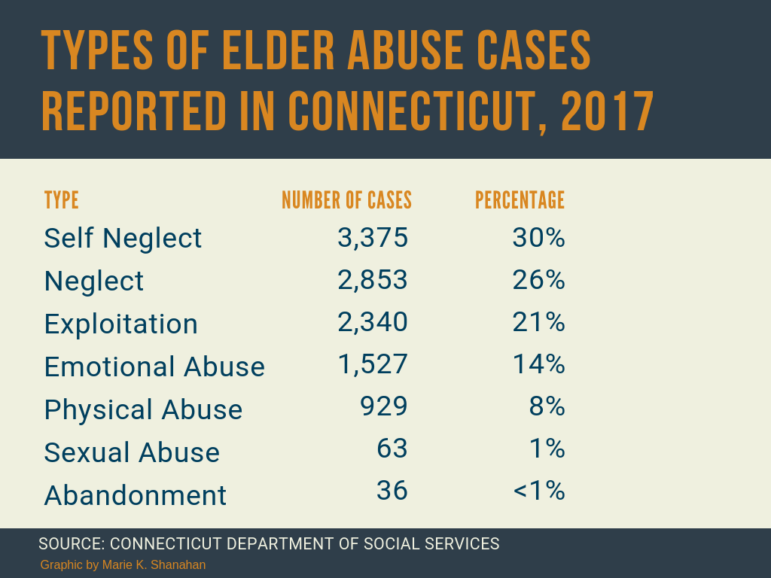

In 2017 alone, the state Department of Social Services (DSS) received 11,123 reports of elder abuse and decided that 7,196 warranted an investigation. That year, self-neglect—when adults are unable to provide for their own basic care—was the most common type of elder abuse reported to DSS, at 30 percent, followed by neglect by others, financial exploitation, emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse and abandonment.

“It’s all trending up,” Dorian Long, DSS director of social work services, said.

Some of the recent cases investigated by DSS Protective Services for

the Elderly are chilling. A 74-year-old man who was frail, thin and

prone to falling was living alone in a home infested with cockroaches

and mice. The in-home care of a woman over 90 was stopped for nonpayment

because her niece had spent her aunt’s money on her own household. An

87-year-old man confused about his finances had his utilities shut off

after his son had spent his money instead of paying the bills.

Long’s 68 social workers helped all the seniors find in-home care, a new

conservator or better housing—whatever they needed to escape the

neglect or abuse.

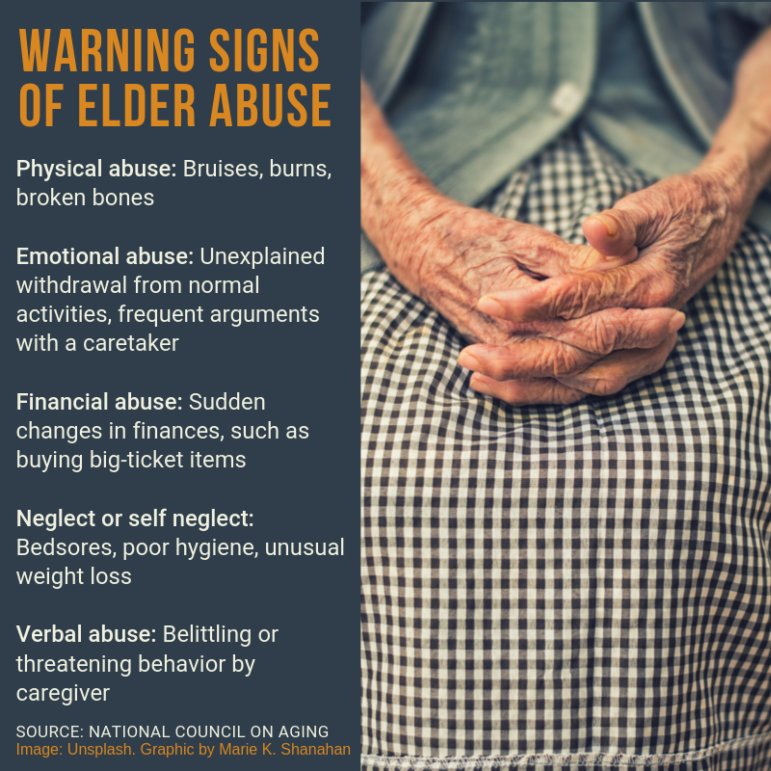

Sexual abuse of the elderly is also on the rise, Long said. In the past, DSS would investigate three or four cases a year, working with police, and now it typically handles 40 cases a year. Scams targeting the elderly are also increasing, she said. Seniors can avoid becoming victims by staying involved in their communities. “The more you are isolated, the more vulnerable you are,” Long said.

The Justice Department estimates that 1 in 10 American seniors are abused, and state officials say the problem is likely to grow as the population in Connecticut—already the sixth oldest state—rapidly continues to age.

Complaints about abuse in Connecticut nursing homes, residential care homes and assisted living facilities rose by nearly 15 percent between 2015 and 2017, said Mairead Painter, the state Long Term Care Ombudsman.

Experts say the numbers of elder abuse complaints may be rising due, in part, to greater awareness, but still, many cases are never reported.

“Sometimes individuals are too embarrassed to report it,” Painter said. “Sometimes people are fearful that if they report abuse, they may have to stay longer at a nursing home.”

From Physical Abuse To Romance Scams

The cases of elder abuse seem to be all over the news. In January 2018, the live-in caregiver of an 81-year-old man with dementia was arrested after going on a rampage, breaking a TV and burning papers on a stove, in the man’s apartment in the Rockville section of Vernon.

This January, a Rockville couple in their 70s had several thousand dollars in cash and jewelry stolen when they let in their home men posing as utility workers.

Sometimes the abuse is physical. When she was 69 and living in Meriden, Rita Pompano said, she endured seven months of physical abuse from her husband, Ralph Pompano.

Each day when he told his wife to grab a pillow, the pain would soon follow.

“I knew that was time for my daily beating,” said Pompano, now 76 and living in West Haven. “He’d have me put my face into the pillow so nobody would hear me screaming.”

She escaped with her son Anthony’s help in 2011, only to have her husband threaten him three months later to find out where she was hiding. Ralph Pompano, 74, pulled a gun and fired a shot at Anthony that day before fleeing to Virginia. Two years later, he died in prison.

Bonnie Brandl, director of the National Clearinghouse on Abuse in Later Life, said she has encountered cases like the Pompanos’.

“The abuser may decide their life is being cut short and will become threatening,” Brandl said. “It’s the ultimate act of power and control.”

State Sen. Tony Hwang, R-Fairfield, and four state representatives have proposed legislation to create an elder abuse registry. Similar to the state sex offender registry, it could keep people convicted of such crimes from doing it again, he said.

“We need to be sure our seniors are protected,’’ he said. The bill has been approved by the state legislature’s Committee on Aging and referred to the Senate.

The AARP Connecticut holds workshops across the state to alert seniors about scams, ranging from IRS and sweepstake scams to fake Nigerian princes, said Erica Michalowski, the organization’s associate state director for community outreach.

“We say that the scam artists have gotten the senior into their ether,” she said. “They’re keeping the senior off-balance in a heightened emotional state.”

Betty Bajek, 66, of Prospect, volunteered to educate seniors about fraud for AARP after someone stole her credit card number and charged $1,200. She said romance scams are on the rise as criminals befriend seniors, show a romantic interest in them and then ask for money.

“These con artists prey on lonely people,” she said.

Nationally, financial exploitation and neglect are the most common types of elder abuse. Some states, including Connecticut, count self-neglect as abuse. Julie Schoen, deputy director of the National Center on Elder Abuse, said that is appropriate so those seniors get help. Brandl, of the national clearinghouse, agrees that they need help, but said, “For me, it’s not elder abuse when there’s no perpetrator.”

Unlike children who are abused, seniors can decline help. Long said DSS social workers do encounter some elderly people living in squalor who refuse their services.

“We put on the charm and try to convince them, but as an adult, you have a right to make choices—even bad choices,” Long said. The caseworkers may go back a few weeks later to try again. If the person says no, they have to close the case.

Help Is Available

One of several agencies in Connecticut assisting elders is the CHERISH program in Ansonia, which counseled Rita Pompano after she left her husband. It provides a hotline, court advocacy, safe housing and counseling for victims of domestic violence who are over 60 statewide.

Its coordinator, Mary Jane Liddel, stayed close by as Pompano recounted her story of her husband’s violence. Tearing up briefly, Rita said CHERISH helped her heal. Now, she enjoys freelance writing, cooking for friends and taking road trips with friends.

“I’m just happy that I’m free,” she said.

CHERISH’S 24-hour hotline: 203-736-9944 or 203-789-8104.

To report cases of suspected elder abuse, neglect or exploitation in Connecticut, call the toll-free referral line at 1-888-385-4225; after business hours, or weekends, or state holidays, call 211.

For information about Protective Services for the Elderly, click here.

Support Our Work

The Conn. Health I-Team is dedicated to producing original, responsible, in-depth journalism on key issues of health and safety that affect our readers, and helping them make informed health care choices. As a nonprofit, we rely on donations to help fund our work.Donate Now