By Peggy McCarthy

Recommend Tweet Email Print More

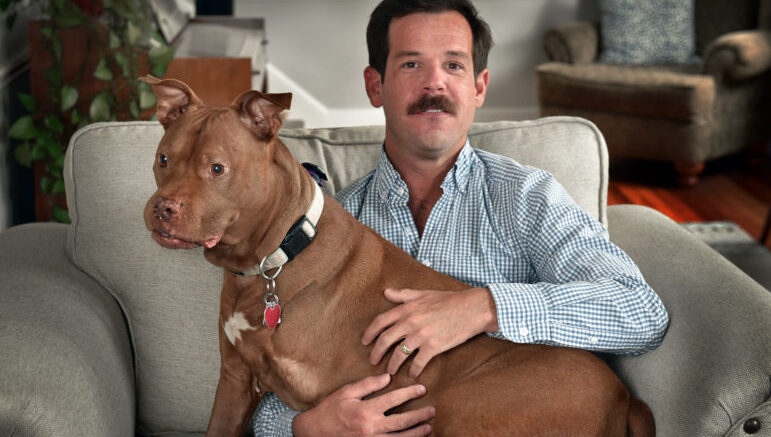

Thomas Burke, his wife, Gretchen Wright, and his emotional support dog Rosie. Burke says Wright and Rosie are a major part of his recovery. Burke is the co-founder of High Ground Veterans Advocacy, which trains veterans to advocate for local, state and national policies. Melanie Stengel Photo.

Food makes Thomas Burke nauseous. Burke, an ex-Marine, won’t eat in front of people because he’s likely to vomit. He barely gets down meals and never finishes what’s on his plate.

He’s struggled with anorexia and bulimia at different periods for more than a decade, and like many other veterans with eating disorders, he attributes them to his time in the military.

Burke, of Weston, said that in his Marines’ basic training, drill instructors didn’t eat in front of the troops, which he saw as a message that eating is a weakness. In Iraq and Afghanistan, he went days without eating while focused on military missions. In Afghanistan, he witnessed children being blown up by a roadside bomb, and he had to pick up their body parts. It triggered a suicide attempt, longtime suicide ideations, and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). He saw himself as someone who didn’t “deserve to eat,” he said.

Veterans’ eating disorders are associated with exposure to trauma and pressure to meet military weight and fitness requirements, said Dr. Sara Rubin, a psychiatrist who heads the Eating Disorders Program at VA Connecticut Healthcare. Also, women who have been sexually assaulted in the military are disposed to eating disorders, she said.

“It’s not a coincidence that a lot of folks who come through and see me [for PTSD] have eating disorders as well.” There is “a lack of attention to eating disorders” in the military.

— Dr. Sara Rubin, psychiatrist

According to Robin M. Masheb, a Yale Medical School psychologist and researcher for the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), “so many veterans seem to struggle with their eating and body image, but go unrecognized.”

A study of post 9/11 veterans found that bulimia, binge eating and atypical anorexia nervosa (AAN) were associated with depression, anxiety, PTSD, insomnia and a lower quality of life. AAN has symptoms of anorexia, including starvation and extreme fear of weight gain, but without dangerous low weight. The study led by Masheb of more than 1,100 veterans was the first to examine AAN in veterans. It found that 14% of women and 5% of men had probable AAN, “a clinically significant eating and mental health disorder.” The study also showed 6% of the women and 3% of the men had bulimia (binging and purging), three times the civilian rate.

Eating disorders can also result in death. A study by Deloitte Access Economics found that 10,200 people die each year because of an eating disorder. Anorexia nervosa has the second-highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disorder after opioid use disorder, and one in five deaths among people with anorexia is a suicide, according to the National Eating Disorders Association.

The VA Eating Disorders Program was established in 2019, shortly before the COVID-19 pandemic began, affecting participation, Rubin said. Patients have to be referred by clinicians, who often don’t detect signs of eating disorders, particularly among overweight patients, she said. So far, 29 men and 26 women have been referred. Services include diagnosis, remote group sessions, cognitive behavioral therapy, nutritional counseling, psychotherapy and medication.

Masheb, director of the national VA’s Veterans Initiative for Eating and Weight, said eating disorders have been masked in military and veterans’ populations because most research has focused on white, teenage girls and young women, leading to erroneous beliefs that men, older and overweight women, and people of color don’t have eating disorders.

Robin Masheb’s study was the first to examine atypical anorexia nervosa in veterans. Yale School of Medicine Photo.

Masheb is working on several studies addressing eating disorders. They include designing mechanisms so the VA can screen patients for eating disorders, which it doesn’t do now; determining appropriate treatments for veterans with binge eating disorder; separating treatment of binge eating disorder and bulimia in the military from weight management; and training VA providers to identify eating disorders.

The Connecticut National Guard has created a Fitness Improvement Program to help soldiers struggling with weight and fitness, according to spokesperson Capt. David Pytlik. He said it focuses on sleep, nutrition, mental health and exercise, adding that if a soldier’s eating habits raise concerns, they are referred to behavioral or medical practitioners.

Burke said women veterans have told him they starved themselves before military weigh-ins and struggled to get back to required weight after giving birth. He knows of people who added muscle by weight training and were considered overweight. He called for a change in the military culture so that self-care, including nutrition, is valued.

Masheb led a study that showed a relationship between changing eating habits to meet military weight standards and binge eating and eating pathology later in life. The study reported that nearly 24,000 soldiers were discharged between 1992 and 2006 for exceeding maximum body fat limits.

Burke was diagnosed at the VA with an eating disorder about four years ago, but the focus was on his physical health and didn’t include mental health care. He now sees a private therapist who addresses the psychiatric issues and physical needs associated with eating disorders.

“I’m in a better place, but I still struggle quite a bit,” he said.

It’s been a journey. After returning home from the military, he tried to eat more, but he didn’t know how. “I couldn’t regulate my food intake,” he said. He became bulimic, eating all his groceries in one sitting, then vomiting. When he was a wrestler at Sacred Heart University, he repeatedly broke and fractured ribs brittle from malnourishment. The pain frightened him into wanting to learn to eat properly and add muscle by weightlifting. He said his starvation was partly connected to a desire to be thin, a characteristic of anorexia.

“My feelings of what I deserve very much have to do with eating and caring for myself, doing what I need to do to be happy,” Burke said. His wife has used trial and error to find foods that appeal to him. He also drinks protein shakes.

At 5 feet 7 inches, he now weighs 150 pounds, up from a low of 120. And at 32 years old, his life is full. He graduated from Yale Divinity School and is associate minister for children, youth and families at Norfield Congregational Church in Weston. He is co-founder and treasurer of High Ground Veterans Advocacy, which trains veterans to advocate for veterans’ issues. He got married last year. He said his wife, Gretchen, has helped him “become healthier, mentally and physically,” and his service dog, Rosie, calms his anxieties.

Burke had a recent setback when the Navy Discharge Review Board rejected his application for a discharge upgrade from other than honorable (OTH) to honorable. He said his discharge status was based on marijuana use after the children’s deaths in Afghanistan. The OTH is “absolutely connected” to feeling like “a person who doesn’t deserve to eat,” he said with tears in his eyes.

For help with eating disorders, contact Nationaleatingdisorders.org.

Support Our Work

The Conn. Health I-Team is dedicated to producing original, responsible, in-depth journalism on key issues of health and safety that affect our readers, and helping them make informed health care choices. As a nonprofit, we rely on donations to help fund our work. Donate Now