By Elizabeth Heubeck

Recommend Tweet Email Print More

Wilfredo Estrada, a 71-year-old New Haven resident and native of Peru, says getting colonoscopies is “muy necesario.” His father died from colon cancer at age 65, and he knows family history plays a role in cancer risk.

Estrada described his odyssey fighting polyps detected by preventive colonoscopy screenings, which he has been getting since 2018. During the most recent procedure, Estrada says, the doctor found and extracted 29 polyps, all noncancerous.

When asked if he tells people he knows how important it is to get screened, Estrada responded through his interpreter, “No. It’s not something I like to share with others.”

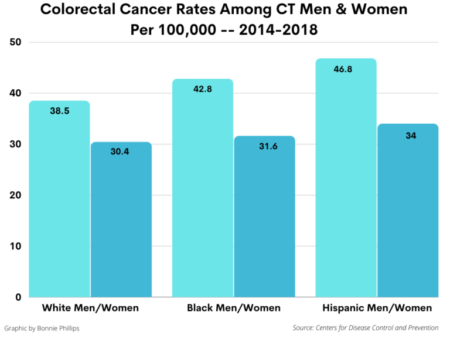

By staying current with colonoscopies, Estrada is doing his part to avoid becoming a cancer statistic. In Connecticut, colorectal cancer is the fourth most diagnosed cancer in men and women, and is the fifth deadliest type of cancer, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data captured in 2018, the most recent year for which these statistics are available. Black men and women have higher death rates than whites and Hispanics, the CDC data show. And it’s not a problem that’s going away.

According to national research, people born in 1990 are twice and four times more likely to be diagnosed with colon and rectal cancers, respectively, compared with similarly aged adults born around 1950, like Estrada.

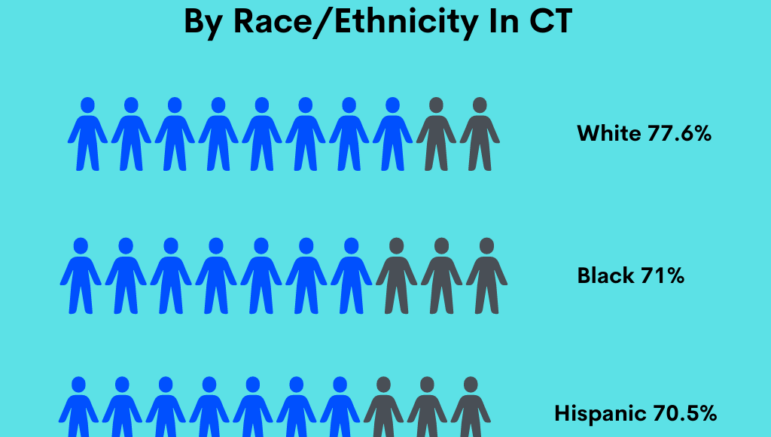

But despite strong evidence showing that screening methods such as colonoscopies—the “gold standard” of preventive colorectal cancer screenings—significantly reduce the risk of death from colon cancer, fewer than 80% of age-eligible Connecticut residents are up to date on them. Black and Hispanic residents lag behind their white age-eligible counterparts, and fewer than 50% of the uninsured among the state’s residents are up to date on these life-saving screenings, according to a state fact sheet on colorectal cancer screenings prepared by the CDC.

But efforts by health care and advocacy organizations are working to close these disparities among Connecticut residents.

There is some debate within the medical community whether non-invasive at-home testing is as reliable as colonoscopies for those in low risk groups.

Patient Navigators Support Screenings

While a desire for privacy may prevent patients like Estrada from discussing with others the importance of screening for colorectal cancer, organizations like nonprofit Project Access New Haven work to spread the news. Under the nonprofit’s Uninsured Specialty Care program, Project Access has a Screening Colonoscopy Navigation Program in partnership with Fair Haven Community Health Care that serves primarily black and brown community members who don’t have access to care.

“Our patient navigators reach out to patients, explain who we are, schedule the colonoscopies, and we work with the hospital to go through the process. There are so many different layers that can prevent patients from getting that screening.”

While patient education is critical to encouraging cancer prevention measures, the obstacles don’t always lie with the patients themselves, say some experts.

Systematically Identifying Patients At Risk

Dr. Xavier Llor directs Cancer Screening and Prevention, part of Community Engagement and Health Equity at the Smilow Cancer Hospital, Yale New Haven Health. The 1-year-old program is working to bring systematic changes to how patients are referred for cancer screenings and, when advisable, genetic testing.

Llor cites Lynch syndrome as an example. Caused by an inherited gene mutation, the syndrome increases one’s risk for colorectal and other cancers and is one of the most commonly diagnosed cancer syndromes in Latinos.

“We are working to make sure that everyone who could have a cancer syndrome is diagnosed,” Llor said. It is well-documented, he says, that patients of color receive genetic testing far less frequently than white patients, a circumstance that multiple studies attribute to referral bias.

Llor points to system-wide measures recently implemented at Yale New Haven that work to counter referral bias. In one, the pathology department analyzes tumors removed from patients using a simple pathology test. If a tumor is found to contain a specific alteration that is commonly seen in tumors of patients with Lynch syndrome, the pathology department—working in concert with the health care system’s informatics team— sets an automated system in motion that results in reaching out to the patient’s provider to make a referral for genetic counseling and testing.

Previously, Llor explains, pathologists would note the need for genetic testing but wouldn’t always make the actual referral. “If we do the extra work, we can get there,” Llor said. Using this new more systematic method, he says, referrals to genetic testing have jumped from 40% to 80%.

“Instead of waiting for our culture to change, we [at the Smilow Cancer Hospital] keep working to change our culture,” Llor said, adding, “Very few people are hesitant about screening when you talk to them.”

Pandemic And New Screening Recommendation Create ‘Perfect Storm’

Two recent occurrences have created a higher-than-normal backlog of colorectal screenings. The pandemic forced medical offices across the state to close temporarily and created apprehension among countless patients about in-person medical visits for non-emergency purposes. Then in May, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force lowered the age recommended for starting routine colorectal cancer screening, from 50 to 45 years of age.

Michael Barry, vice chair of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, says several factors influenced the decision. These included data showing that an estimated 10% of colorectal cancers are now occurring in people under 50, and that routine colorectal screenings starting at age 45 could help save additional lives. If the numbers continue heading in their current direction, researchers suggest that colorectal cancer could lead cancer-related deaths among people 20 to 49 years old within the next 10 years, even sooner for young black people, whose colorectal cancer incidence and death rates are higher than among any other race/ethnicity.

Despite the new lower age preventive screening recommendations, health care providers say many patients didn’t appear eager to return to pre-pandemic [screening] routines.

“Even once our endoscopy centers opened, we saw significant and concerning trends in patients wanting to postpone these” colonoscopies, said Lindsey Meehan, director of operations at Hartford HealthCare’s Digestive Health Center. “Patients electively decided to push out colonoscopies and other routine cancer screenings.”

But rather than turning attention to COVID-19 vaccination and away from preventive screenings, some health care systems got creative about focusing on both.

“We used our vaccine clinics as an opportunity for community outreach for all cancer screenings,” said Meehan, who observes that Connecticut’s preventive screening grades are better than most states. “But unless it’s 100 percent, we still have work to do.”

People can visit www.TimeToScreen.org or call toll-free 1-855-53-SCREEN (1-855-537-2733) to learn more about cancer screenings and find a convenient location.

Here’s a column by CTwatchdog.com on Colonoscopy or FIT? Doctors Disagree.

Support Our Work

The Conn. Health I-Team is dedicated to producing original, responsible, in-depth journalism on key issues of health and safety that affect our readers, and helping them make informed health care choices. As a nonprofit, we rely on donations to help fund our work. Donate Now