By Gregory B. Hladky

Daryl Perch Photo.

A hazy sunset from western smoke captured by Daryl Perch in Stonington.

Connecticut’s weather on May 25, 2016, was hotter than usual for that time of year, reaching a high of 91 degrees. The winds were out of the northwest at about 10.5 mph and state air pollution officials weren’t expecting anything unusual.

Then the state’s air pollution monitoring network went ballistic.

Ozone sensors across Connecticut began recording “off-the-chart readings,” Paul Farrell, the director of air planning at the Department of Energy and Environmental Protection, recalled. State experts were shocked. “That was not at the point of the year you expect to get high ozone readings here,” Farrell said.

Farrell and other experts quickly realized what had happened: smoke particles from a wildfire some 2,600 miles away in Alberta, Canada, had drifted into Connecticut from the upper Midwest and New York. Air pollution warnings immediately went out, urging people with at-risk conditions like asthma and heart disease, the elderly, pregnant women, and young children to stay indoors.

It wasn’t the first time a major wildfire had created air pollution problems in Connecticut and climate scientists are warning that increasingly hot, dry conditions in North America are likely to make such events more frequent.

The massive fires now ravaging the West Coast have sent smoke plumes all the way to this side of the continent, but state experts say that smoke isn’t currently a health risk for Connecticut residents because of how high it is in the atmosphere.

They also warn a change in wind and weather could bring those particles down to levels that could prove dangerous to people with existing respiratory conditions. They are urging people in high-risk categories to keep checking the state’s air quality reports.

“Hopefully, all this will stay in the high atmosphere,” said Dr. J. Samuel Pope, a pulmonologist and director of Hartford Hospital’s medical intensive care unit. “But it is very hard to know.”

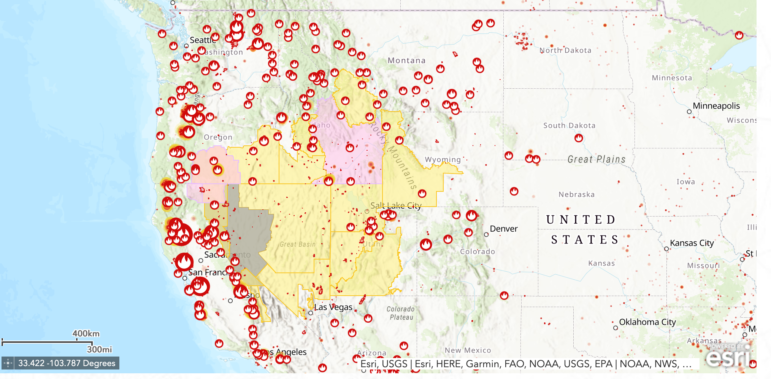

Wildfire activity in the west, tracked by ESRI.

Connecticut’s high ozone season tends to come during the hottest summer days when sunlight interacts with pollution from cars, power plants and smoke particles near the ground to create what is commonly known as smog.

A 2016 study led by Yale University researchers collaborating with scientists from Harvard and Colorado State University estimated that more and bigger West Coast wildfires would create added smoke pollution dangers for an estimated 82 million people. The report forecast that the number of U.S. residents dying as a result of wildfire “smoke waves” could double by the end of this century, to an estimated 40,000 deaths a year.

The most recent U.S. Climate Assessment predicted that hotter, drier weather in the future could result in dramatic increases in the frequency of major wildfires by 2050.

“Climate change is increasing the frequency and severity of western wildfires,” said Meg Harvey, an epidemiologist with the state Department of Public Health. “This fact makes it important for Connecticut to be prepared for the possibility of future impacts from western forest fires or forest fires closer to Connecticut.”

“If wildfires become more common, you’re going to see increased health impacts in Connecticut,” Farrell said. Pope agrees: “If this is going to create more intense wildfires, it’s going to cause more health problems.”

The people with the highest health risks from wildfire smoke pollution tend to be children, pregnant women and the elderly.

Health and environmental experts warn those higher health risks are likely to hit hardest in low-income urban areas where people of color already have the state’s highest rates of asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), bronchitis and other respiratory diseases.

“It has a really inequitable impact here in Connecticut,” Samantha Dynowski, Connecticut director for the Sierra Club, said of any additional air pollution caused by wildfire smoke.

Pope said inner-city residents also “have less access to health care in general.”

DEEP has an air monitoring network in Connecticut and publishes on its website a daily “Air Quality Index” to warn when pollution could present a hazard to the public.

Connecticut health risks from wildfire smoke are already higher than in many parts of the U.S. simply because our air pollution is worse. Much of that poor air quality comes from having so many cars and trucks in such a small geographic area, but Connecticut’s problems are made worse by industrial pollution floating in on air currents from states like Pennsylvania and Ohio.

Support Our Work

The Conn. Health I-Team is dedicated to producing original, responsible, in-depth journalism on key issues of health and safety that affect our readers, and helping them make informed health care choices. As a nonprofit, we rely on donations to help fund our work.Donate Now

Related Stories

- Dead Fish, Condoms, Brown Foam: Sewage Has Chokehold On Black Rock Harbor On April 25, 2018, Patrick Clough walked onto a dock at Fayerweather Yacht Club on Black Rock Harbor in western Bridgeport. He looked down.

More From C-HIT

- Disparities Industrial Farming Outweighs Willpower In Obesity Crisis, Experts Say

- Environmental Health Wildfire Smoke Likely To Have Increasing Impact On Health Of Those Already At Risk

- Fines & Sanctions UPDATED: Coronavirus In Connecticut

- Health Care Health Bills’ Failure A Bitter Pill For Health Care Proponents

- I-Team In-Depth Pandemic Deals Another Blow To Nursing Homes: Plummeting Occupancy