By Carol Leonetti Dannhauser

Recommend Tweet Email Print More

Carol Leonetti Dannhauser Photo.

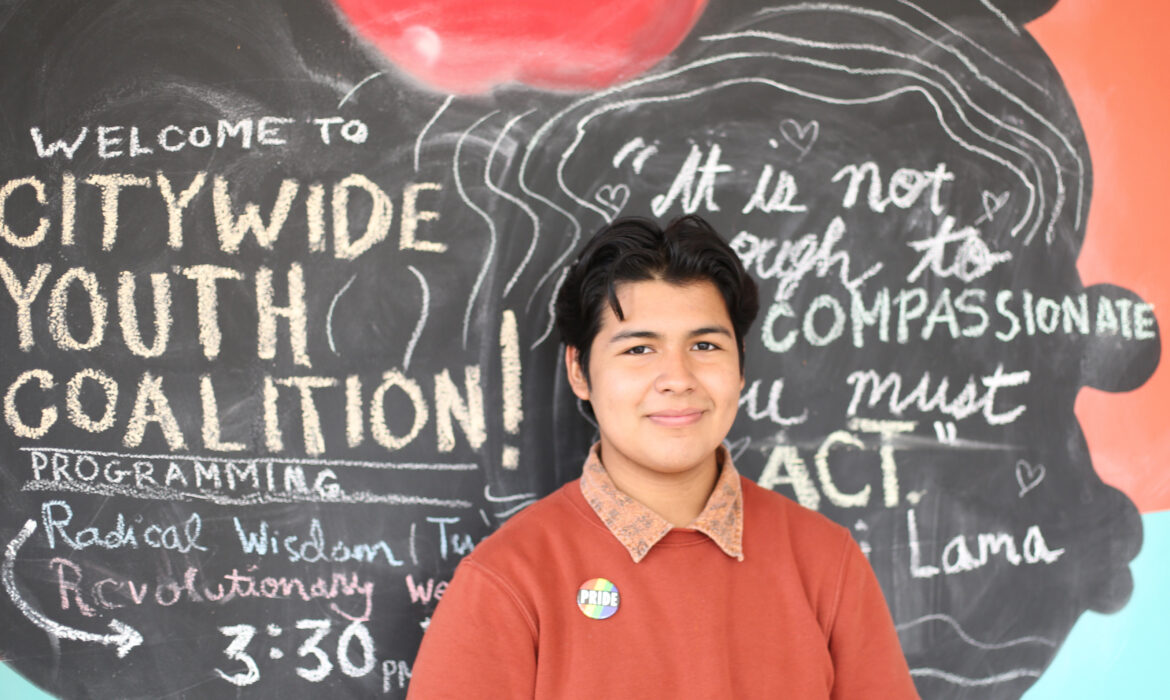

Alex Lopes, 16, a student at High School in the Community, and leader of the school’s Gender Sexuality Alliance, wants toilets and urinals enclosed from floor to ceiling so students have privacy and feel comfortable.

One by one, speakers lined up at a New Haven Board of Education meeting last fall to support a policy ensuring “the safety, comfort, and healthy development” of LGBTQ youths in school. Parents, teachers, advocates and students came forward, most with an anecdote and a plea: to protect children in New Haven schools who are bullied, unable to find safe bathrooms, and are referred to by the wrong pronouns—all because of their gender identity.

Following the testimony, the school board unanimously approved the Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Youth policy. Among other things, it grants students the right to change their name and gender identity on school records without parental permission; the right to be called by their preferred name and pronoun in school; the right to keep this information private without school staff telling parents or peers; access to gender-neutral bathrooms and more.

By the end of the school year, what changes had the policy affected?

Not many, some students said.

Look closer, said the school staff.

“Some of this is intangible; you wouldn’t be able to see it,” said Typhanie Jackson, the executive director of student services for New Haven Public Schools and a lead writer of the policy.

The next step, they all agreed, is to build on what’s working when August rolls around.

A Matter Of Life Or Death

From the moment little ones are told at school to line up by gender or are directed to a particular bathroom by gender or greeted by a well-meaning teacher with “Good morning, boys and girls,” versus, say, “Good morning, everyone,” school can be an emotional and physical minefield for someone whose gender identity differs from the one assigned at birth, reports Tony Ferraiolo of New Haven, a transgender man, educator and trainer.

Tony Ferraiolo of New Haven, a transgender man, educator, and trainer.

“I’m working with kids who are 6, 7, 8 who have suicidal ideations and are doing self-harm,” Ferraiolo said. “How can we expect a child to give 100 percent at school if they can’t be 100 percent of who they are?”

Ferraiolo has trained educators in gender awareness for nearly two decades. Such enlightenment can be a matter of life or death. LGBTQ youths in gender-affirming schools report lower rates of attempting suicide than their peers, according to The Trevor Project 2022 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health.

New Haven’s policy calls for all staff—from teachers to custodians to cafeteria workers—to be trained in gender sensitivity, but the training is voluntary. Only six of New Haven’s 44 public schools have requested training, which is paid for with a grant from the Yale Medicine Pediatric Gender Program.

“When you start using words like ‘mandate’ and ‘accountability,’ those are four-letter words. That makes it polarizing, in a way,” Jackson said. Better to have a voluntary conversation about a school’s goals and objectives, about “addressing the whole child, and making sure we have equity across any kind of spectrum.” For some staff members, “a little more information might change their minds and heart.”

That change didn’t happen for Tahnee Cookson Muhammad. As her son was coming to terms with his gender identity at Betsy Ross Arts Magnet School, he asked his teachers and classmates to refer to him using the gender-neutral pronouns “they” and “them.” Instead of deepening understanding, though, the pronouns became derisive. While some teachers obliged, one refused, thinking the youngster believed he was more than one person. “Some students were purposely using wrong words to bully, 100 percent,” Cookson Muhammad said. When incidents occurred, she or her son would report them, “only to have things happen again,” she said.

Cookson Muhammad wondered how a child could be emotionally able to learn in school if they were privately wondering, “When I go to the bathroom, if I go to this one, will I get picked on? If I go to that one, will someone do something to me?”

She spoke from her home in Branford, where her family moved when the bullying and harassment became too much. “My son has grown a lot, but the experience was very damaging,” she said. Her son now attends a private school in New Haven “that is very consciously aware.”

Bathroom Pass

Nationwide, nearly 60% of LGBTQ students feel unsafe at school, and about a third miss classes as a result, the GLSEN 2019 National School Climate Survey reports. Many avoid gender-segregated spaces, such as bathrooms, altogether.

In many Connecticut schools, LGBTQ students can use the bathroom in the nurse’s office, “but what’s the message there? I’m walking into an environment where people are sick,” Ferraiolo said.

Carol Leonetti Dannhauser Photo.

Dave John Cruz-Bustamante, the student representative on the New Haven school board, envisions schools in which teachers, students and staff celebrate a shared culture without “forcing students to assimilate into an identity they’re not familiar with.”

New Haven’s policy calls for single-user restrooms, but “that is a long-term facilities question,” Jackson said, “and a longer-term goal.”

Alex Lopes, 16, is a rising junior at High School in the Community and a transgender teen. In middle school, he avoided the bathroom at all costs. Was he allowed to use the bathroom of the gender he identified with? Would he be safe in there? He didn’t know. “I had to wait until I got home,” he said.

At HSC, a single-user bathroom for students exists, but it is on a far side of the second floor, difficult to reach between classes and often locked, with the key in the main office. Fortunately, the teacher who advises the school’s Gender Sexuality Alliance (GSA) allows all students to use a bathroom in her classroom when needed.

Lopes, who founded and leads his school’s GSA, has proposed in a letter to the school board enclosing all toilets and urinals from floor to ceiling, “so that each student has their own privacy and feels comfortable.” In addition, he is lobbying to remove hall doors to bathrooms to reduce the risk of harassment and bullying, he said, and to help students “feel safer.” Lopes cited a survey in 2017 by the Human Rights Campaign and the University of Connecticut that found that 51% of transgender youths “can never use the restrooms or locker rooms that match their gender identity.”

Lopes and other students have met with administrators to discuss gender-neutral bathrooms since the beginning of the school year, “but nothing has happened. A lot of students just don’t feel heard,” Lopes said. “I’m transgender and pansexual. I want to create a safe place for people like me.”

Lopes has had a lifetime of not feeling heard. In foster care since age 6, he has lived in more than a dozen foster homes, all the while trying to come to terms with his gender identity. In one conservative Christian home, the mother forbade him to cut his hair short because it “wasn’t feminine.” He was told to participate with the girls in elementary school because he was designated female at birth. In eighth grade, he finally met a transgender student “who explained everything. I was like—wait!—that’s what I’ve been feeling!”

Lopes came out as transgender and adopted a new first name, Alex, which his new foster family at the time supported. But he said his school and caseworker refused to acknowledge the change. During a hospital stay at Yale in 2019, he “mustered up some courage” and asked hospital workers to call him by his chosen name versus the name on his birth certificate, and they obliged. “I finally felt validated,” he said.

Buoyed by his experience at the hospital, Lopes emailed his teachers at HSC at the beginning of his first year, explained that he was transgender, and asked that teachers call him by his preferred name, not the name on his record. While many of them did, getting his record corrected still hasn’t happened. His current foster family calls Lopes by his preferred name, but he knows peers who are too afraid to reveal themselves to their families.

Carol Leonetti Dannhauser Photo.

Tahnee Cookson Muhammad moved to Branford and removed her son from a New Haven public school when the bullying and harassment of her son became too much.

He supports the school board policy’s promise to keep gender identity private. “All kids want to be validated by the people who are in charge of caring for them, whether they’re teachers or parents or foster parents or biological parents or whatever,” Lopes said, “but some parents are very against this. They may tell their kids, ‘No, you’re not this, you’re this.’ Some parents may even physically hurt kids or will throw their child out of their home.” Indeed, 40% of homeless youths are LGBTQ, according to the advocacy group True Colors United. Teachers outing a student overrides a student’s ability to assess danger at home and act accordingly.

While Lopes welcomes the new policy, he’s surprised that the school board never notified students. “I would think it should have been a cause for celebration,” Lopes said, “but there wasn’t much publicity about it.”

The lack of a launch was deliberate, Jackson said. “This kind of work I wouldn’t perceive as having a big rollout.” She said that the policy simply extends the school board’s work to make schools inclusive for all without singling out a group. Plus, some of the guidelines “have to be unpacked further,” she said. A rollout could lead to a scorecard tallying what’s been done and what hasn’t. “At the end of the day, it’s very hard to quantify,” she said.

Staying Ahead Of The Curve

The new policy was crafted from recommendations by the non-partisan Connecticut Association of Boards of Education (CABE). When Connecticut outlawed discrimination based on gender identity or expression, the model CABE policy, “Accommodating Transgender or Gender Non-Conforming Students,” followed, with a revision in 2017. “We try to stay ahead of the curve,” said CABE’s Executive Director Bob Rader.

While the intersection of gender identity and school “is a new concept for many people,” Rader said that is not the case for him. About 15 years ago, Rader’s son Dustin came out as transgender while attending Glastonbury High School. “It helps when the school is supportive. It enables everybody to be who they are without suffering consequences from something over which they have no control, like the color of their skin,” Rader said.

Carol Leonetti Dannhauser Photo.

David Weinreb is a teacher at Elm City Montessori School and member of the city’s LGBTQ+ Youth Task Force since 2018. “We want to make sure that student preference and safety are prioritized,” Weinreb said.

Only seven out of 48 school districts in Connecticut CABE have adopted transgender and gender-non-conforming policies, Rader said. “Some of our members are conservative, and some are liberal. Maybe some feel it’s not appropriate for their district. We have to strike a balance. Our job is to recommend; their job is to decide what’s best for their district. They have a choice.”

The New Haven school board didn’t act when CABE first released its recommendations, said David Weinreb, a teacher at Elm City Montessori School and member of the city’s LGBTQ+ Youth Task Force. Instead, the board was “publicly quiet about LGBTQ issues. There is such inertia around fixing these things.” The Task Force formed in 2018 has been lobbying the school board ever since to help LGBTQ students feel safe. “We want to make sure that student preference and safety are prioritized,” Weinreb said.

He is encouraged by the move to include LGBTQ-related questions in the annual School Climate and Wellbeing Survey. “We know LGBTQ students are suffering, but we don’t have the data. We hope the survey substantiates the anecdotal. There’s something backward about creating a policy based on no data.”

Hoping For A Shared Culture

Dave John Cruz-Bustamante is a rising junior at Wilbur Cross High School who identifies as gay and genderqueer. He serves on the Citywide Youth Coalition and was elected in June as the student representative on the New Haven Board of Education. While the school board’s new policy is “a step in the right direction,” he said, he would like to see consequences for failing to abide by the policy and would rather they repair than punish.

Take homophobic remarks on the bus or bullying in the hallways, each of which he has experienced. “There’s a systemic element in that, yet there’s no way now to address that harm without the offending student getting kicked out of school,” Cruz-Bustamante said. “While consequence is important, consequences should mean repairing that harm. In my opinion, New Haven Public Schools are against restorative justice initiatives that work. They preach this, but they don’t put the concrete systems in place. In practice, you see a lot of scapegoating and a lot of punitive consequences.”

Cruz-Bustamante said only one teacher in the 16 classes he’s taken at Cross has asked students for preferred pronouns. “Sometimes it’s arrogance and outright hostility, and sometimes it’s ignorance; people are less likely to hurt each other if they know each other,” he said.

He envisions schools in which teachers, students and staff celebrate a shared culture without “forcing students to assimilate into an identity they’re not familiar with. Trying to fit everybody into gender binary ends up erasing somebody’s identity. You end up cutting up pieces of person’s personality.”

Cruz-Bustamante said that while he didn’t notice any changes at Cross following the policy’s passage, he appreciates the effort. “Even if it doesn’t have a huge effect, you can at least point to it and say this is your duty.”

Alas, Jackson said she wishes that people would pay more attention to what’s been accomplished: “more GSAs, more inclusive language around the buildings, pathways to deal with bullying behavior—versus focusing on what hasn’t been done. We’re looking at how to continue to protect rights and to do better.”

Support Our Work

The Conn. Health I-Team is dedicated to producing original, responsible, in-depth journalism on key issues of health and safety that affect our readers, and helping them make informed health care choices. As a nonprofit, we rely on donations to help fund our work. Donate Now