By Carol Leonetti Dannhauser

Cloe Poisson Photo.

Kyle Jones of South Windsor says she feels more at home in her body since beginning her transition in early 2020.

Kyle Avery Jones had recently come out as transgender to her parents and friends when her final semester at the University of Connecticut began in January 2020. She wore androgynous clothes to school, sought out gender-neutral bathrooms, and limited her socializing to queer-friendly weekend gatherings off-campus.

“Everyone in my classes assumed I was a dude. I didn’t want to show up one day with a face full of makeup and a dress on. I was literally counting down to the end of the semester. I thought, ‘Once I finish college, I won’t have to do this anymore,’” said the 22-year-old Realtor from South Windsor.

Then COVID-19 struck, moving college online. Suddenly, Jones was staring herself in the face all day on a computer monitor, her anxiety rising with each class. “I was very distraught about having stubble on my face; it was an area of gender dysphoria for me. I would shave two or three times a day to make it extremely smooth. There was a lot of stress going on, and I just had to fight through it.”

She turned to feminizing hormone therapy to help light the way.

‘Very Jarring’

While COVID-19 has shuttered businesses and quarantined countless people in Connecticut and beyond, it has also motivated many transgender individuals such as Jones to begin gender-affirming hormone therapy, experts say. The reasons vary from the chance to transition away from gossiping co-workers, to realizing what’s important in life when the death count is daily news, to coming to terms with the self-image looking back during online work, school and socializing sessions.

“Ninety-nine percent of the time, gender dysphoria is what leads someone to begin hormone therapy,” says Layne Gianakos, director of programming and community relations at Anchor Health Initiative in Stamford and Hamden, which specializes in health care and wellness for the LGBTQ community. “Usually, you’re not looking at yourself speaking at all. It’s very jarring.”

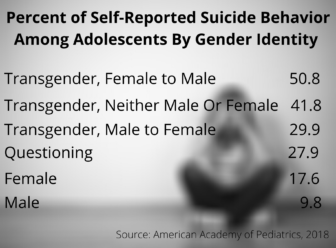

Gender dysphoria is the psychological distress that results from a disconnect between how a person identifies sexually and their assigned gender at birth. “It’s very similar to trauma,” Gianakos said, and it can be life-threatening, particularly for young people. In fact, more than 50 percent of transgender adolescents in the United States who were designated female at birth but identify as male have attempted suicide, according to a 2018 report from the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“This is a public health crisis that not nearly enough people are addressing,” Gianakos said.

Transgender hormone therapy addresses the disconnect. Our endocrine glands secrete hormones into the bloodstream, and these hormones regulate a host of body functions, including those that can help a person better align with a gender. Many transgender women, such as Jones, undergo feminizing hormone therapy. This includes testosterone blockers and estrogen to promote breast growth, alter skin texture, redistribute weight and slow body-hair growth.

Many transgender men undergo masculinizing hormone therapy. This includes taking testosterone to help develop muscle mass, thicken vocal cords, redistribute weight and increase body hair.

Increasingly, transgender youngsters are taking hormone blockers to delay the onset of puberty.

Katy Tierney, an endocrinology specialist and medical director of the Middlesex Health Transgender Program in Middletown, says that COVID-19 has rocked the transgender community as it has the community at large.

“Either it makes you feel incredibly unstable, or it gives you the opportunity to make all the changes you ever wanted to make. A lot of transgender people were like, ‘This is the time. It’s now or never.’ I’ve had patients in their 80s start their transition.”

— Katy Tierney

When Tierney joined Middlesex Health six years ago, there were no transgender-identified patients in the system. “Now we have more than 1,200,” she says. Her appointments are filled three months in advance.

‘Little Baby Steps’

One of Tierney’s patients is Paula Degree, 73, the former pastor at a Congregational church in the Oakville section of Watertown. “When I came out as transgender, the night I told my council was the last time I entered that building.” There were “a couple of church bullies” who made it clear that now that she was a transgender woman, Degree wasn’t welcome on the pulpit. “Oakville is kind of a blue-collar village, and they were just not handling change well. I kind of knew that would happen.” Degree had already been kicked out of her own home. “When I came out to my now ex-wife, she physically pushed me away and told me to get out of the house.” Two of Degree’s three adult children have stopped talking to her.

Paula Degree says she is “elated” by her transition.

Degree visited with a gender therapist prior to starting hormone therapy. “The first several sessions were very tense. I was under the impression that I had to convince my therapist that I was transgender.” That wasn’t the case, however; Degree discovered that she could identify however she chose. With Tierney’s help, Degree started with an estrogen patch and went from there. “Transitioning is a whole series of little baby steps that when you’re doing them are huge. You just feel so elated,” Degree says.

Tierney’s clients do not have to label themselves to seek care. For many transgender patients, this is the first time that they are not pinned to a gender. “The minute we know what genitals our child has, we have set out a plan for them,” Tierney says. “It sort of boggles my mind how hard we hold on to that gender expectation. I don’t have any expectations about any pronoun or what they’re wearing. Whatever is safe for them is what works for me. They can wear a suit and tie and take estrogen, and that’s fine with me.”

The transgender program at Middlesex Health is one of at least six hospital-run transgender programs in Connecticut. UConn Health opened its Transgender Medicine Services in the thick of the pandemic last year. The program includes a dedicated gender-affirming hormone therapy clinic in Farmington, in addition to services such as cosmetic surgery, urological care and voice therapy.

Due to COVID-19, these programs now offer telehealth services, which many transgender people credit with easing the path to transitioning. For years, lack of transportation, access to transgender-friendly doctors’ offices, even hostility in some medical settings left many transgender individuals skittish about seeking services. Thanks to telehealth, patients can seek care from wherever they want, wearing whatever they choose, presenting however they feel comfortable. Even at places such as Anchor and Planned Parenthood, which served the LGBTQ community long before hospital programs came on the scene, most new transgender patients during COVID-19 have opted for telehealth.

Statistics vary on how many transgender people live in Connecticut. Data derived from a 2017 National Institutes of Health survey estimate the number of transgender adults here at 7,000. A 2016 report by the Williams Institute at UCLA, however, hikes that figure to 12,400. Last month, the state’s LGBTQ Health and Human Services Network launched its first-ever needs assessment survey, which could result in a more accurate count.

Gianakos suspects the numbers may be higher than estimated. Anchor Health fielded 42,961 client calls from March 1, 2020, to Nov. 30, 2020, up about 10% from the same period in 2019. Some calls came from concerned parents who, sequestered at home instead of at work all day, came face-to-face with their transgender child’s struggles. “Parents are saying, ‘I didn’t realize how miserable my child was,’” Gianakos says. “I’ve been dealing with one high school right now that is not respecting a teen. It’s an absolute nightmare.”

Incredible Joy

Angel Roubin of Essex is a clinical psychologist who provides help to transgender clients, many under 18. She says that COVID-19 has underscored to many transgender children how little control they have in their life.

“These kids are on Zoom every day for school. It’s a constant reminder of ‘I don’t fit in. I’m not who I want to be. I’m living a lie. I’m literally flunking all my classes. I can’t function. I’m so distraught.’ It’s so overwhelming. It’s a trap you literally can’t escape.”

— Angel Roubin

Roubin began working during the pandemic with a teenager who “lives in a very unsupportive home. This person is already wearing a (breast) binder. He has breast growth. He is already getting a period. Menstrual cycles are horrendously hard, and so is showering. The parents have seen this kid day in, day out, suffering.”

The teen begged his parents for masculinizing hormones, but the father worried that the youngster would change his mind down the road. The father had a change of heart in November, Roubin said, when the teen told him, “‘Every day that I’m not on testosterone, irreversible things are happening to me.’ The kid was saying ‘I can’t live like this much longer.’ The person transitions, but the family has to transition, too.”

Not every family changes, and this has wreaked havoc on living situations, especially during the pandemic, and especially for transgender adults ages 18 to 26. Says Gianakos, “I’ve been seeing a huge increase in housing instability for trans people since the first stay-at-home order. Clients are living with family, they start hormones, and the family says ‘no, absolutely not,’ and they get kicked to the curb.” He estimates that 23% of transgender people have been homeless in Connecticut and, with shelters operating at about a third of their capacity, “it’s a really dire situation.”

Some parents have discontinued health insurance coverage for their transitioning offspring. Couple that with skyrocketing unemployment due to the pandemic and many young transgender people have found themselves scrambling for health care. “Some people lose their job, lose their insurance—and lose their hormones,” Degree says. “A lot of people turn to the black market.” Indeed, without insurance, money for a co-pay, or a doctor to write a prescription during quarantine, some transgender people on hormone therapy have resorted to transgender-friendly Google documents, Facebook groups and subreddits to try to crowdsource their hormones from peers with a surplus stash.

In June, the federal government repealed provisions of the Affordable Care Act that protected transgender people from sex discrimination and ruled that a person’s sex is determined by their biology at birth. Connecticut, however, mandates that health insurance cover transgender medical care.

“I’m lucky; my mom has really good insurance,” says Jones, who graduated from UConn with a business degree in May. She’s a real estate agent now and will be responsible for her coverage once she ages out of her mother’s policy.

Cloe Poisson Photo.

Kyle Jones at home.

Nearly the same day that Connecticut’s stay-at-home order took effect 10 months ago, Jones began her hormone therapy. Prescriptions in hand, she went to CVS, waited for her friend Olivia to show up for moral support, then swallowed her first testosterone blocker. The pair marked the occasion back at Jones’ house with a beverage that Jones, a former bartender, concocted: colorful liqueurs stacked atop each other to look like an LGBTQ rainbow. Jones followed the drink with an estrogen chaser.

Two weeks in, Jones “started to feel more relaxed,” she says. A couple of weeks later, her acne disappeared. At three or four months, she noticed breast tenderness. She kept up her laser hair removal and went clothes shopping as her weight redistributed itself, her pants too snug in the hips and too loose in the waist.

“I have breasts now. They’re still growing. And the fat in my face is more feminine,” she reports. “I’d never viewed myself as attractive, but it happened for the first time a couple of months ago—that feeling of appreciating your body and who you are. That’s the most amazing thing because I never thought that would be the case. The joy that that brings is really incredible.”

Support Our Work

The Conn. Health I-Team is dedicated to producing original, responsible, in-depth journalism on key issues of health and safety that affect our readers, and helping them make informed health care choices. As a nonprofit, we rely on donations to help fund our work.Donate Now

Related Stories

- E-Reading, Screen Time for Young Children Draw Scrutiny The Mitchell branch of the New Haven Free Public Library tries to be at the forefront of whatever products are trendy or new. That means offering e-books for patrons of all ages and providing computers for children who want to conduct research online or play games.